A B R I E F H I S T O R Y OF

A N N A H A L L

The building and golden era of Anna Hall ( 1852 - 1909 )

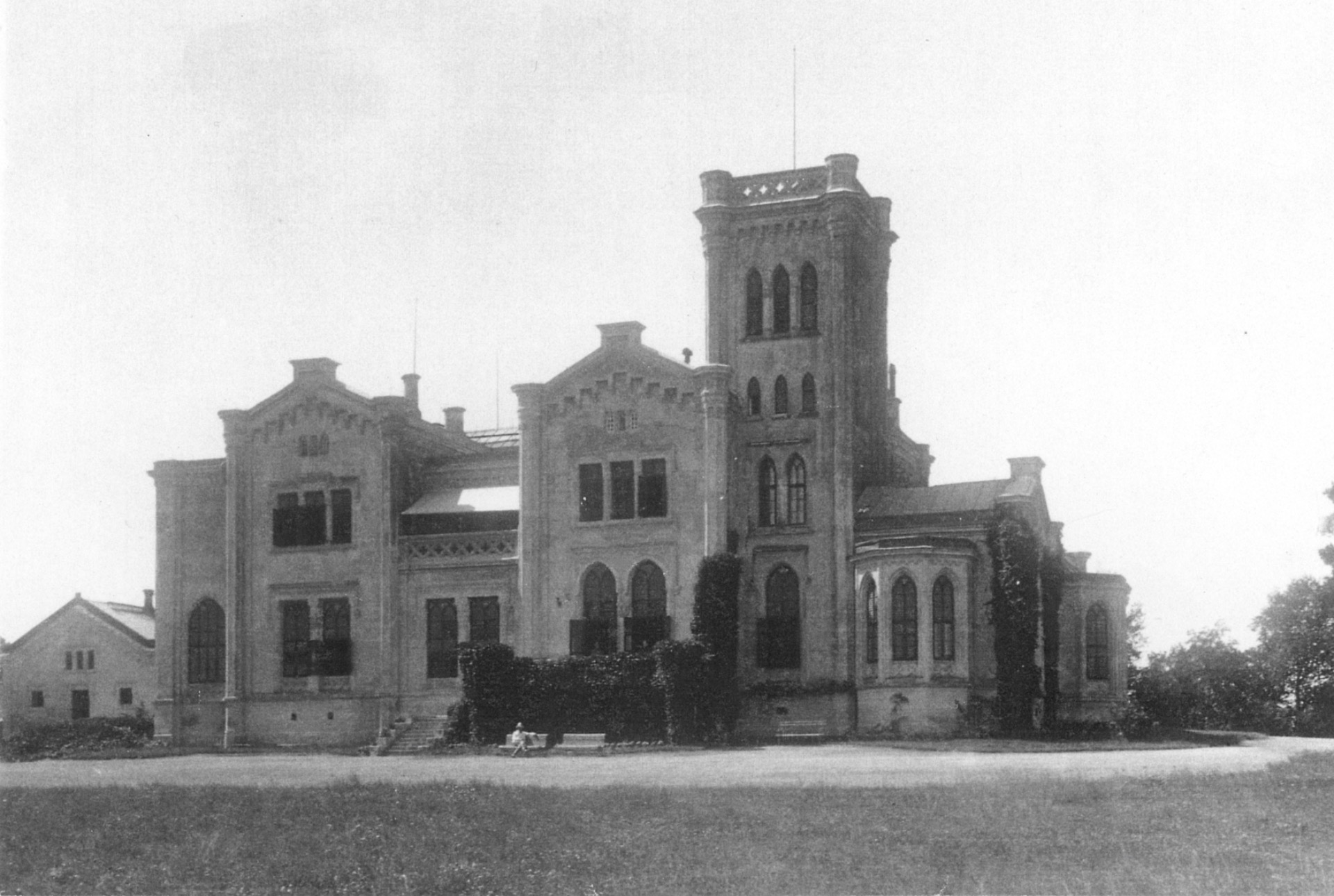

Count Pál Ferenc Zichy built his manor on his estate in Nagyhörcsök, located in the heart of the Mezőföld region, based on the designs of Antal Wéber. Construction began in 1852 and lasted only three years. The Neo-Gothic manor, enriched with Moorish influences, was named Anna Hall after his wife, Countess Anna Kornis of Göncruszka.

However, the construction did not stop. As the family grew and their social life expanded, Anna Hall continued to develop under the plans of Miklós Ybl, featuring the most modern architectural solutions of the age.

The manor soon became the intellectual and social centre of the family. Balls, salon evenings, hunts and charity events followed one another, while the estate also gained a reputation as a model of modern agricultural farm. The innovative tools of the farm, the carefully designed park and the evenings hosting artists of the time all contributed to the unique atmosphere. The family's library, salon life, and art collection earned the Nagyhörcsök estate a significant prestige.

Thanks to this, the most esteemed nobles, artists and politicians of the time visited Anna Hall.

By the turn of the century Anna Hall had become a defining venue for the cultural and social life of the area where English elegance met Hungarian tradition in perfect harmony. However, in 1909 the death of Count Pál Ferenc Zichy brought the golden age of the founders to an end. The house remained in family hands, but its brilliance slowly began to fade.

.

Guardians of the heritage ( 1910 – 1938 )

After the founders, the heirs of the manor — relatives, cousins and more distant branches of the Zichy family — took over the management of the estate. The building was no longer the home of lavish balls and hunts, but rather a quiet family residence. The park remained well-kept, the farm operated, but the atmosphere of the era was characterized by restraint and slow change.

The First World War and the Treaty of Trianon shook the financial and social situation of the Hungarian aristocracy. The family still preserved the heritage of their ancestors, but social transformation and growing economic hardship made it increasingly clear that the manor's former splendor could no longer be maintained.

These were silent decades of memories. The radiance of the past still shimmered faintly within the walls, but the premonition of decline already hung over the building.

The years of demolition ( 1939 – 1942 )

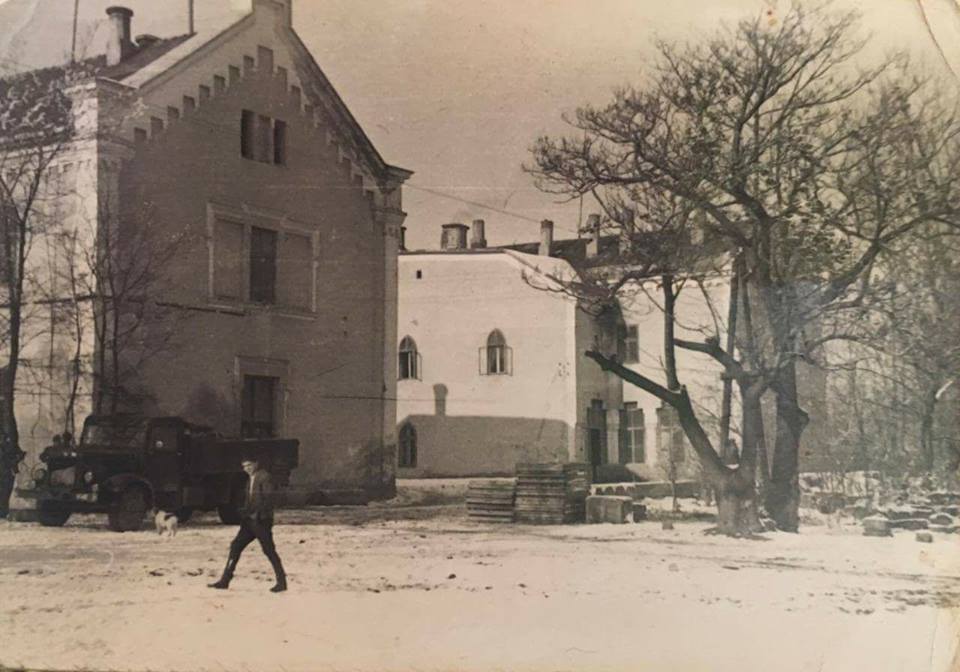

The shadow of the Second World War sealed the fate of Anna Hall once and for all. The heirs decided to demolish part of the manor.

Between 1939 and 1942, the valuable architectural elements, such as ornate stone carvings and railings, were neatly placed in the park — though most of them were removed during the war and in the following years. The walls of the main wing gradually vanished, leaving behind only a few outbuildings and the ancient trees of the park as silent witnesses to its former grandeur.

By the time the war broke out in full force, the once romantic residence had become only a shadow of its former self.

.

.

The storm of war ( 1944 - 1945 )

In the autumn of 1944, the inhabitants of Nagyhörcsök had been watching for days as bombers flew overhead toward Budapest. Although the village itself did not suffer a direct air raid, the approach of the front became increasingly evident. On 6th December 1944, at 8 o'clock in the morning the first Soviet soldiers appeared in the village. Locals observed them from bunkers and shelters, and despite all language barrier, the soldiers approached in a friendly manner — they lifted children into their arms, asked for and received food, and often returned from battle singing.

In the following months, Nagyhörcsök became a true battlefield, changing hands several times between Soviet and German forces. The villagers joined the Soviets in repairing roads and bridges digging bunkers.

A particularly memorable and dramatic episode occurred on February 12, 1945, near the "Csíra Stable". The retreating German troops had left behind two snipers, whom the Soviets tried to eliminate after artillery preparation. The civilians — including women, children, and livestock — who had sought refuge in the stable, endured hours of fighting as bullets whistled over their heads, while in the midst of the chaos a woman gave birth to a child. Thirty-six Soviet soldiers were killed in the clash, and the two German snipers were eventually shot.

The battles took a heavy toll: the school, the farm buildings and homes were destroyed, as well as a significant part of the rich livestock. Even after the fighting many people dies because of the mines left behind.

Anna Hall did not escape the devastation either. Its furnishings and remaining books were burned, and after a rocket hit rendered the western wing unsalvageable, it was permanently demolished.

The fighting finally ended on 21st March 1945,, when Soviet forces expelled the Germans. Traces of trenches can still be discovered in the forests surrounding the castle - silently preserving the memory of the war.

Nationalization and the State Farm era ( 1945 – 1994 )

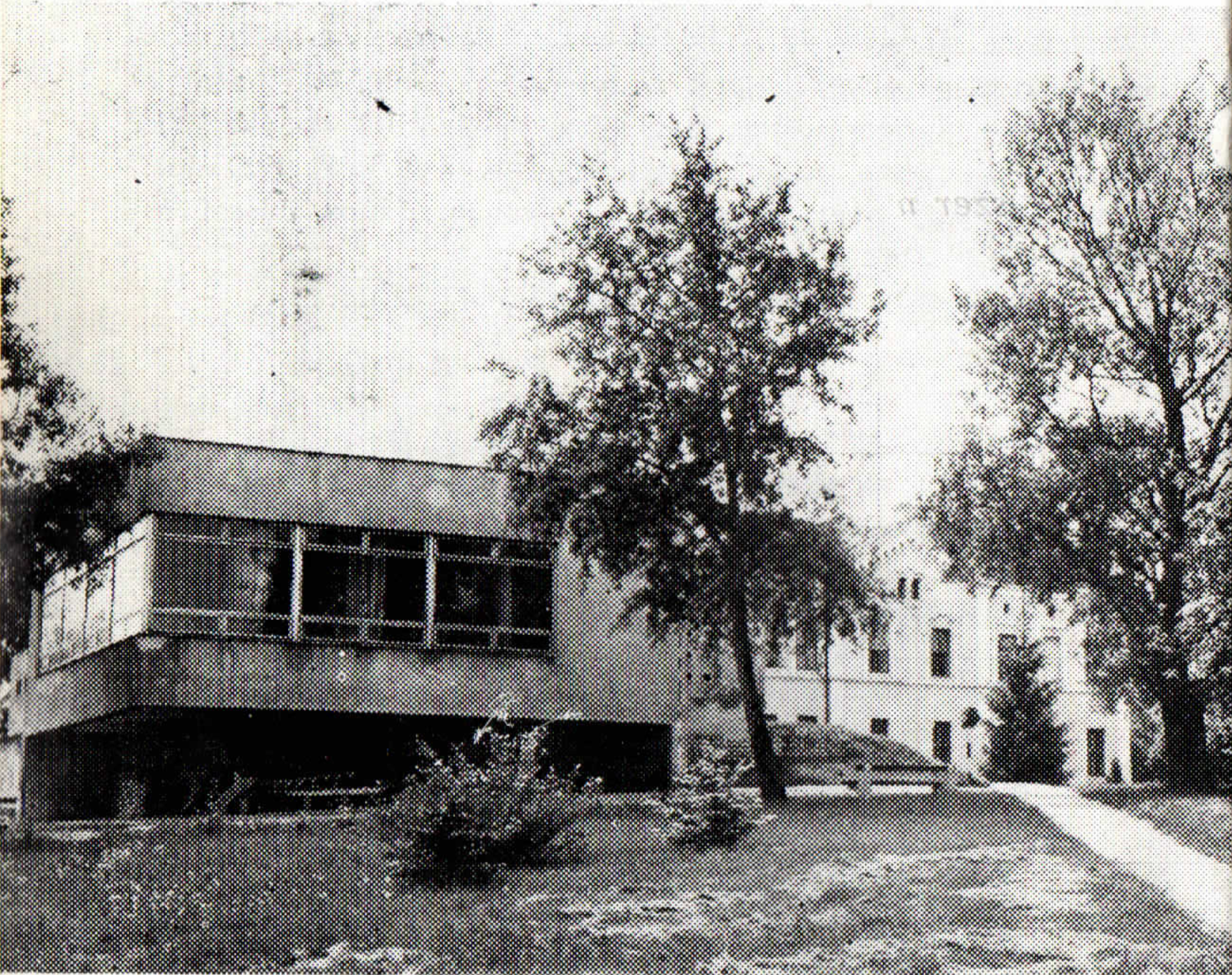

The decades following the war did not spare Anna Hall. After the front lines had retreated, the interior of the manor gradually fell into decay: the remaining furniture and ornaments were taken away, the condition of roof and walls deteriorated year by year. Eventually, the building became state property and was not placed under the management of a collective farm, but of a State Farm.

In 1953, the remaining buildings were renovated to meet contemporary needs, and the headquarters of the State Farm moved here. On the site of the former representative main wing, a socialist realist ("szocreál") style industrial kitchen and dining hall were constructed — the main walls still stand today, silently marking the era of transformation.

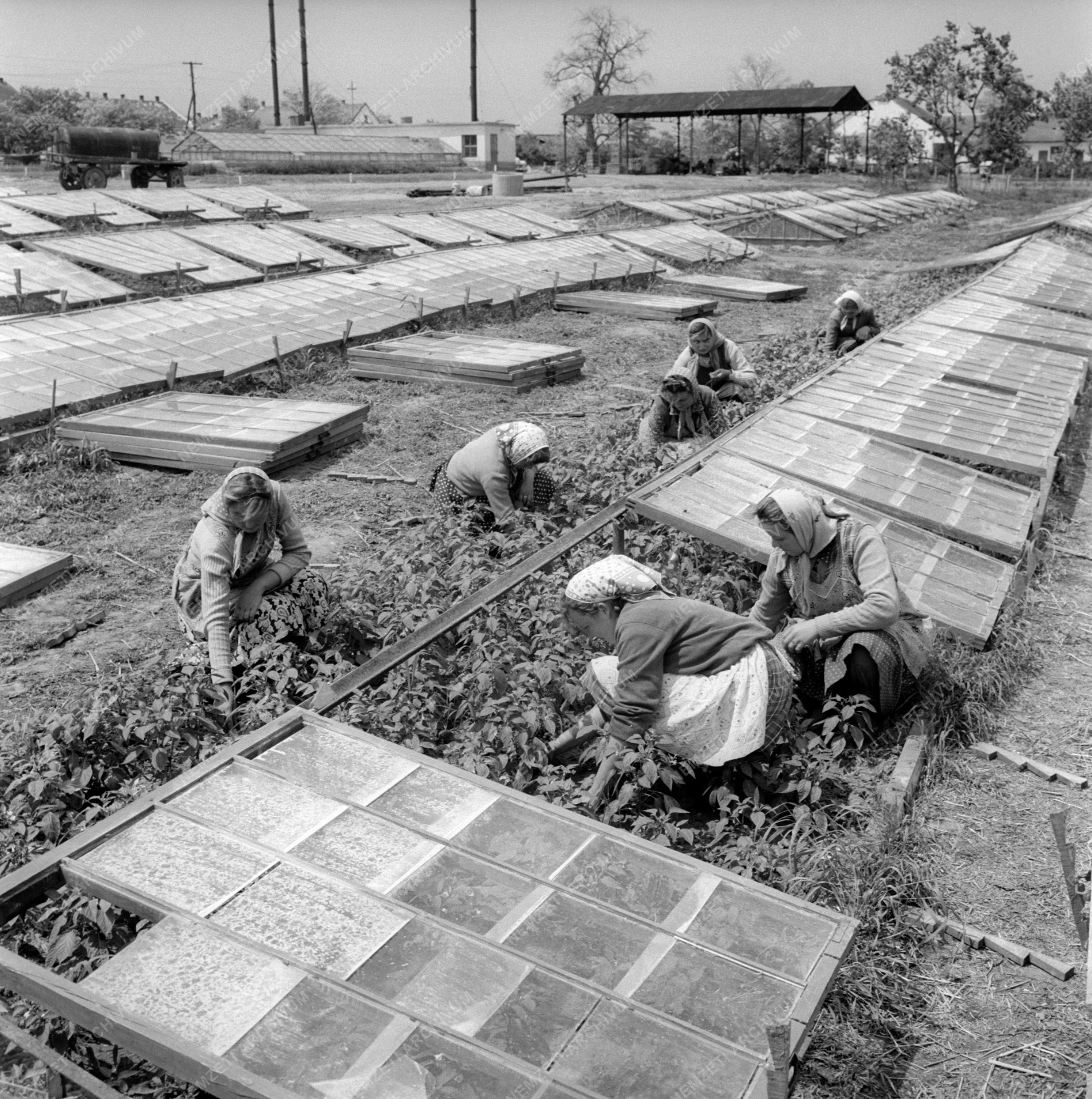

The farm was not only a workplace, but also a centre of cultural life for the surrounding region. A folk dance group and an amateur theatre troupe entertained the workers, often performing in neighboring villages as well. Sports life was also remarkably active: in 1951, the farm's football team won the district championship, and its athletes excelled in running and long jump.

A football pitch was built in the manor park which was inaugurated by the opening match of the local team against the Budapest Honvéd SE. Later, a tennis court, a rose garden, a club room, a bowling alley, and an open-air stage were also established within the park.

The daily life of the farm followed the rhythm of large-scale agricultural production. The number of permanent employees reached 400 people, supplemented by about 150 seasonal workers. The industrial kitchen regularly provided hot meals for more than five hundred people each day.

Later, the Nagyhörcsök State Farm became part of the Mezőfalva Agricultural Combine, with which it operated until 1994, when privatization was completed. The traces of this era — the socialist-realist buildings, the sports field, and the remains of the old rose garden — still remind us of the time when Anna Hall served not only as an economic but also as a vibrant community centre in the heart of Mezőföld.

.

.

The road to ruin ( 1994 – 2017 )

The political transition brought no peace or revival for Anna Hall. Although the remaining parts of the building passed into private ownership, and ambitious restoration plans were outlined — envisioning a refined hotel within the former manor — the project started under unfavorable circumstances. The slaughterhouse operating in the old stables posed a serious obstacle, while the economic crisis quickly drained the available funds.

The abandoned reconstruction not only halted progress but accelerated decay. In the years following privatization, the condition of the building deteriorated year by year: the roof leaked like a sieve, the ceilings collapsed, the plaster crumbled from the walls. The stone and brick materials of the manor were taken away as building material; its ornamentation slowly vanished, and its facade faded, losing its former elegance.

The history of the southern wing was a separate chapter. A slaughterhouse was established in the former agricultural section — operating continuously until 2015.

The once magnificent park turned into a wild bush: the decorative trees grew old or were cut down, and the carefully designed pathways disappeared without a trace.

The legend of the old Anna Hall was still alive in the memories of the locals, yet in reality the building slowly became a pile of ruins. Year by year, it drifted closer to complete destruction, as if it were merely waiting for its final demolition.

Renovation ( 2018 – ∞)

At the turn of 2017–2018, the fate of Anna Hall finally — and we hope permanently — took a positive turn. During these years, we managed to purchase the remaining parts of the building in several stages, with the intention not only saving it, but also to giving it a new and worthy purpose.

At the time the structural reinforcement and the restoration of the park could finally begin.

Since then, the renovation has been processing steadily, within the limits of our means. Though we still have decades of work ahead of us, we are preserving this small but precious fragment of the past, step by step, brick by brick.

.

Today, Anna Hall is far more than a building. It serves as a venue for classical music concerts, chamber exhibitions, literary evenings, and community gatherings, at the same time a living family home and one of the centers of the estate.

Through its spirit, it brings to life a community of people connected to the manor — devotees of heritage preservation, supporters, artisans, visual artists, musicians, and visitors who love the arts.

The continuously reborn Anna Hall, rising from its ruins, pays tribute to the past while opening space for the culture of the present — proving that even after the storms of history, renewal is always possible.